I have been chronically ill, with varying levels of severity, since 2011. For two years I have been too ill to work even part time, and I must spend a great amount of my time at home. Now, due to a deadly pandemic, many of my able-bodied friends find themselves in a similar yet different position. Grief and “FOMO” pour over me in torrents as I am reminded of the vast chasm between my life and what my peers recognize as a life, and I wonder how I could possibly communicate it all.

But why is my sorrow surfacing so painfully now, at a time when I arguably find myself in good company? Now all the world is limited like me. Now they grapple with similar questions to me – how to define their worth outside of their productivity, how to spend days where they can’t just leave home for fun, and whether the health care system will be there for them if they get sick. Now they have a taste of what it might be like. Isn’t the chasm closing a little?

I’m finding it’s more complicated than I could have imagined. But the easiest answer I can give right now is that I am watching people simultaneously mourn the loss of a lifestyle I lost access to long ago, whilst also indulging in at-home activities I have lost the ability to do.

The mass mourning I hear my able-bodied counterparts partake in – over their loss of in-person social contact, of concerts and comedy shows and nights at the movie theatre and pub crawls, of hugs and tickles, of a big vacation they had planned – hits a numb wall of protective indifference in my brain. Some of these are things I barely ever got to experience as an adult, and certainly rarely without physical consequences. Others I lost the ability to do more recently and am still grieving for afresh.

And then there’s the at-home activities they are doing and posting on social media. Things I pine for. The jigsaw puzzles that hurt my neck too much. The DIY projects that I lack the dexterity for. The rekindling of a passion for playing a musical instrument, something that I can technically still do but usually only up to five minutes daily. The snuggling with pets that I am now too allergic to own. The cozying up to significant others and children that I lack. The gluten-filled comfort snacks and alcoholic drinks that my body rejects.

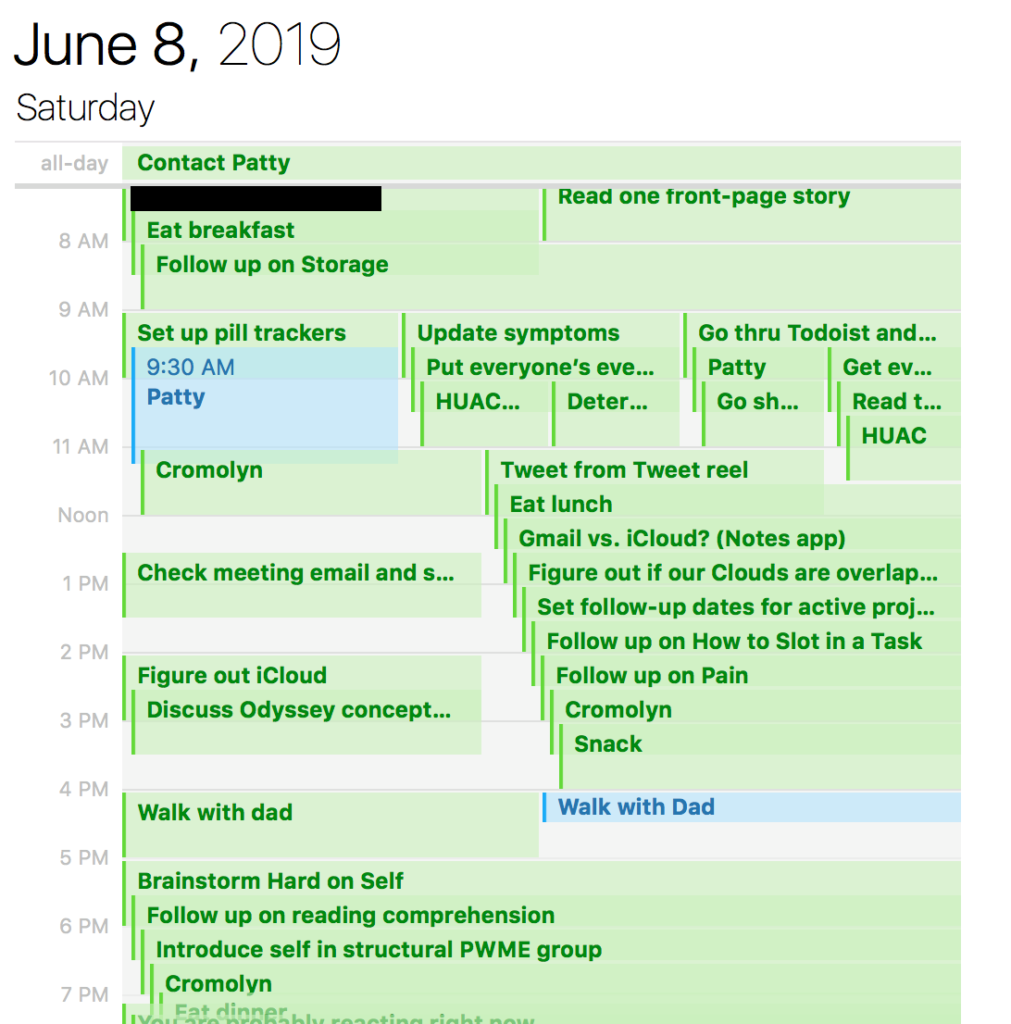

Even the housecleaning and organizing projects that I simply lack the strength for. The cooking that I can’t do. The Netflix binges and movie marathons that I cannot do (on a very good day, I can get through a single movie, but usually not uninterrupted). The reading that I cannot do. The video games that I cannot play. It’s not just one thing. It’s all the things.

And I am finding that even among disabled friends who are benefitting from the migration of education and live entertainment to the Internet, I sometimes feel left out. Due to cognitive and sensory dysfunction, the etiology of which is not totally clear, I am often unable to pay attention to a movie, lecture, or concert for longer than five minutes.

It is impossible to hold any kind of discussion with a healthy, abled person that won’t touch on at least one thing that I invisibly am unable to do. It’s like I’m missing an entire life.

But normally, I am very happy to hear from my abled friends all the same. I love hearing updates. I love calling them. For some reason, my brain has an easier time accessing interactive conversation than static entertainment and I welcome this.

But boy was I unprepared for how rudely my grief would be forced out when all those friends finally found themselves digging into the at-home activities I have been sitting at home longing to be able to do for months. Like I’ve been watching the most delicious cake through a glass display for months, always out of reach, and now my friends are all chowing down on that cake without me.

I’m not new to chronic illness, but I am new to the level of disablement I have experienced for the past couple years. It is an unimaginable grief.

And most of the time, I don’t have to work on imagining it. I just live the life I have available to me – tending to my medical needs, staying in touch with friends and offering counsel, savoring the odd thing I haven’t lost like food or music or baths or dancing a little in evenings or chocolate or walking a few blocks outside.

Or I can try reading audiobooks at my impossibly slow pace just to get the feeling back of being in a kind of flow. It doesn’t matter if I would sometimes flunk a basic comprehension test of something I read minutes earlier. Does it?

Oh, and I can write, albeit not consistently. Somehow that’s been spared too.

And my friends and family didn’t abandon me when I became ill, which unfortunately happens to many people in my situation. My support network is the absolute best.

These things aren’t trivial at all. They’d make me the envy of some of my closest chronically ill friends.

I feel tremendous sympathy for my able-bodied friends who have lost jobs from this crisis, as well as those who can’t find needed food and toiletries in grocery stores, and those who will lose friends, loved ones, or – god forbid – their own lives to either coronavirus, or to other health conditions that the medical system becomes too overwhelmed to treat. I feel rage toward my country’s government for its callousness to the mass death and suffering coming our way.

And as much as I am hurting, I know this – if you’re able-bodied, the grief you are feeling now is a normal and natural response to change.

But when quarantine inevitably lifts, and you throw the first parties celebrating your newfound freedom – consider which people are unable to join you.

They are people like me.

Fight so more of us can.

Nora Helfand is a writer and former research assistant. If you like this blog, support her on Patreon here and follow her on Twitter at @nhelfand.

For more reading on the grief associated with chronic illness, I highly recommend the essay, “The Grief Keeps Coming” by Brianne Benness (who helped me edit this piece). I also recommend psychotherapist Kaethe Weingarten’s piece, “Sorrow: A Therapist’s Reflection on the Inevitable and the Unknowable,” in which Weingarten describes the chronic sorrow of four of her clients with chronic illness and disability. Weingarten defines “chronic sorrow” as “a normal, nonpathological state of pervasive, continuing, periodic, and resurgent sadness related to the ongoing losses associated with illness and disability, in this case not loss of an other but loss of self.”