It’s funny how people talk about “getting their shit together.” It’s like, does anyone reach that point of, “Hey guys, you know what? My shit is together. There is nothing more to be done here.” But after this year I feel like I’m pretty damn close. I may in fact have my shit together.

I don’t know why this is coming up for me now. My emotions don’t alway process in sync with dates and anniversaries. But maybe it’s the approach of Rosh Hashanah. Maybe I’m hurtling toward a time when last year, I didn’t think I would make it to 2019, and wasn’t sure I wanted to. Maybe my body knows something I don’t.

A year ago I was terrified I would never feel happy or have any quality of life again. My brain was under constant assault. I described it to my dad as “traumatic stress disorder.” There was no “post-“. The worst fate I could imagine at that time was going through another day as bad as the one I’d just had.

In some of my absolute lowest moments, where I could not function cognitively enough to read a book, listen to a song, or play a computer game, I somehow managed to come up with the idea of hiring someone to coordinate my health care. I was scared that answers to my predicament might be locked inside me, and it would take some serious organization to pull them out. My dad found someone fitting the specs and now I have a patient navigator working for me.

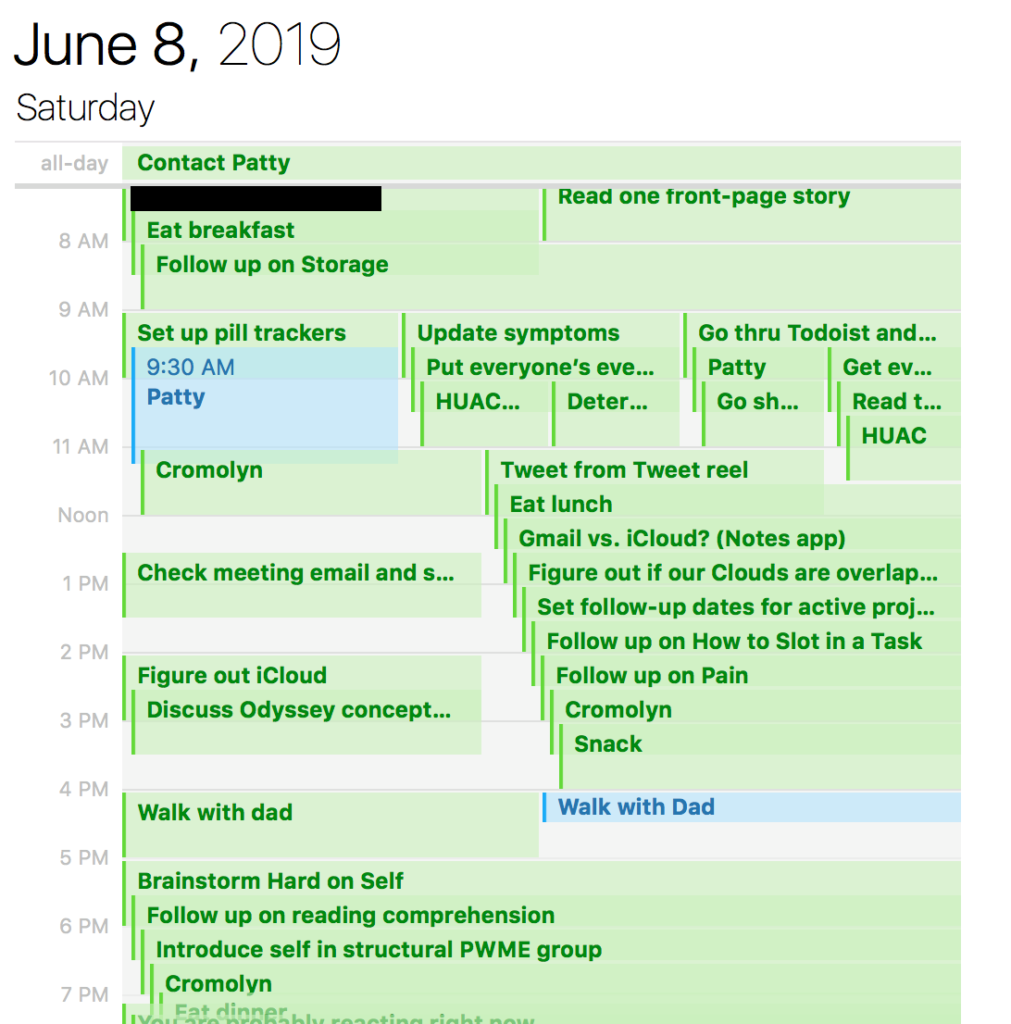

Around the same time, a serendipitous discovery resolved my most distressing symptoms – not enough to work or exercise, but enough to not feel like I was being tossed in a washing machine at all hours of the day. Armed now with a few usable hours, I used them carefully, setting about what my friend Bethany calls “constructing a mental prosthesis.” I used the 7am-8am window to plan the rest of my day, since my brain could not function enough to make decisions the rest of the day. That very simple model grew on itself until I was generating daily to-do lists of upwards of 30 or 40 tasks…and going to bed with them all done. I started developing a detailed complex of protocols to make decisions for me throughout the day, with regular engineering to minimize “crashes” (which were just any time I had to make a decision on the spot, exhausting my reserves).

With a trashed working memory, I made it so the only things I really needed to remember were: look at to-do list app for what to do. Look at “Unscheduled Time” protocol if there’s nothing planned in the app. Write any new ideas or desires in the Notes App – my to-do list app scheduled regular time for me to look through these. For the first time in my life, I was following up on every new idea I had, sorting them into lists that I actually utilized. I was writing regularly. I was listening to new music every day. I was contacting a different friend or family member every day. My calendar every day was full of new adventures, albeit often very small ones that accounted for my frequent inability to comprehend a five-minute video. I learned that doing a very small thing is better than despairing that you can’t do a large thing.

I stopped getting trapped in wishing for what could be. I stopped wishing I was someone else and focused on learning to draw out the gifts I did have. I learned how to break the cycle of decision paralysis, though I often forget. The point is at least knowing how. I’ve learned lessons that I won’t soon forget.

I got in touch with all the people who I was scared my life was too lame for, and made sure everyone knew they were important to me.

I learned to ask for help once I needed help, rather than asking in a way that let on that I already knew the answer. Among other things, this led to actually asking writers to look at my work and to co-writing a play with my aunt.

I realized I could be as proud of the work I put into taking care of me as I had been of my work as a research assistant in the past. I asked my patient navigator to give me a co-author credit on the presentation he made about me for a conference. He said yes. I had, after all, essentially taken my own history for it, putting something like ten to fifteen hours into that part alone. All of a sudden, when I was at social gatherings, instead of saying I had been “working on my health” as usual, I could say I’d co-authored a scientific presentation. About myself! How cool is that?

I quickly found like-minded and like-bodied patients online and dove into that community, and was repeatedly overwhelmed by their kindness and ingenuity. I was surprised and amused by the access I had to prominent advocates I had admired from a distance. “Remember that filmmaker and that author I like?” I tell friends. “I talk to them every day now.” In fear and wonder I started properly nerding out about my medical condition instead of running from it. I fought self-stigmatization telling me not to identify with a life of illness, and wondered how people that brought me so much laughter and validation could be considered a problem.

I set tough boundaries with people around me. I stopped fearing being too much. I let myself be difficult and a handful sometimes. I realized that I was still easier company than the people running my country who made everyone in the world deal with their shortcomings. I stopped lying about how well I was and letting those lies hurt me and confuse others.

I watched my country and planet start the descent into fascist mayhem. I despaired over my government’s indifference to migrants and needed to do something. But unlike in my college years, I didn’t put disproportionate labor on myself in order to get activists to include me. I accepted that giving money can be the most strategic and sensible thing, if not the most gratifying.

I got my family relationships in order and taught my immediate family how to support me with my illness. We started replacing hurt feelings and resentment with humor, organization, and acceptance of conflict. I instituted weekly meetings for us to tackle the ins and outs of my medical care, and it turned out that my care is so much work that this was really warranted, probably from the beginning. I kept weekly assignment charts, and by my count we’ve gotten *forty-five assignments* done since our first meeting on June 14. The medical system is good at creating work for us! So is my body.

I learned that I am not synonymous with my feelings. I learned that objective observation can yield answers if you let go of the outcome you’re attached to. I stumbled upon mind-blowing insights by accident, in a spirit of science. I developed a “spidey sense” and sussed out problems in my medications and environment one by one. I gained my parents’ support as they saw that my suspicions were often correct. I let my body make the rules when medicine didn’t have a clear-cut answer. My body became the boss.

It’s just hitting me how proud I am. At my worst moments in 2018 I remember clinging desperately to a voice I thought I heard from the future that said, I can’t believe how well it turned out. I’m brought to my knees. I don’t know why I was spared. I know I can be a bit of a cheeseball about these things. But I really do make an effort to not exaggerate what happens to me medically. And I know in my bones that whatever I lived through last year was unutterably, intolerably bad.

I feel blessed and pinch myself every day and want the world to know. And yes, I am disabled and I need to bitch about it a lot. Both are allowed to be true. In fact, I think the latter allows the former to happen.

I came away from hell with the intimate knowledge that the human spirit in me, what makes me me, cannot be destroyed. It is worth protecting and caring for. And it also has its shit together.

Nora Helfand is a writer and former research assistant. If you like this blog, support her on Patreon here and follow her on Twitter at @nhelfand.